blorg blorg blorg

This chapter is special in that there are no exercises. Instead, we will take an existing project and study its code and development. Some of the topics covered are:

- State

- Using libraries

- Organizing code

- The principle of “simple”

Get the project

The project is available at:

git clone https://github.com/iloveponies/blorg.gitThe project for this chapter contains multiple tags that identify different phases of the project as it was written. The chapter text will instruct you to check out a certain tag to see the code as it was at a specific point in time.

To begin with, check out the tag initial to see the first version of the code:

git checkout initialThe idea

So far we have programmed various Clojure exercises and at least one larger project (poker hands). It all feels decidedly… unhipster, though. It’s hardly webscale!

We want to write a blog engine, and not just any engine, but one written with Clojure. We also want to use ready-made libraries for writing web applications instead of inventing our own wheel (as satisfying it would be). Additionally, we want to keep the implementation as simple as possible.

Exploratory coding, or why we don’t have tests yet

We don’t really know what we’re doing yet; we’re mostly gluing together existing libraries and defining a very simple model for blog posts. We decide to not write unit tests, and instead implement a prototype instead. We are prepared to throw away this code and reimplement a new version with tests. Alternatively, we might use the prototype itself as the production version and write tests for it after the fact.

Initial implementation

Using the initial tag we can see our first implementation. First, we should take a look at the project definition, which tells us what libraries we are using. The project definition resides in the project.clj file in the project root directory:

(defproject blorg "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT"

:dependencies [[org.clojure/clojure "1.4.0"]

[noir "1.3.0-beta7"]]

:main blorg.core)This definition tells Leiningen that blorg requires Clojure version 1.4.0 and the noir library version 1.3.0-beta7. It also specifies that the namespace blorg.core contains the main function to be called when the user runs lein run.

The first page

Our initial implementation resides in one file, src/blorg/core.clj. It contains very little code, so let us study it. First, let us take a look at the whole file to see the overall structure. You do not need to understand what each bit does yet; we’ll go through each part individually.

(ns blorg.core

(:use noir.core)

(:require [noir.server :as server]

[hiccup.page :as page]))

(def *posts* [{:title "foo" :content "bar"}

{:title "quux" :content "ref ref"}])

(defpage "/" []

(page/html5

(for [post *posts*]

[:section

[:h2 (:title post)]

[:p (:content post)]])))

(defn -main [& args]

(println "> blorg blog blorg")

(server/start 8080))That is the whole file. Let us run the program to see what it does:

blorg$ lein run

Compiling blorg.core

Warning: *posts* not declared dynamic and thus is not dynamically rebindable, but its name suggests otherwise. Please either indicate ^:dynamic *posts* or change the name. (blorg/core.clj:6)

Compilation succeeded.

> blorg blog blorg

Starting server...

2012-05-24 12:50:49.775:INFO:oejs.Server:jetty-7.6.1.v20120215

Server started on port [8080].

You can view the site at http://localhost:8080

#<Server org.eclipse.jetty.server.Server@eaecb09>

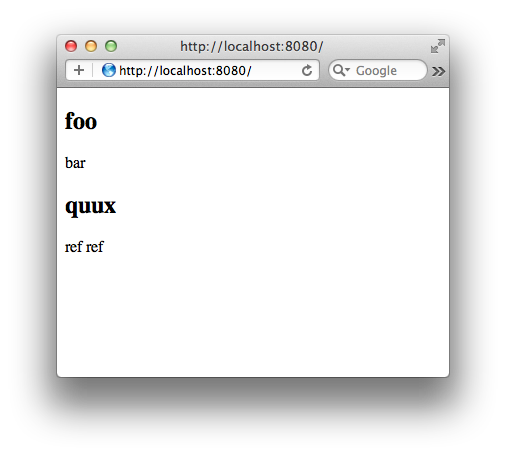

2012-05-24 12:50:49.819:INFO:oejs.AbstractConnector:Started SelectChannelConnector@0.0.0.0:8080The output contains one warning, which you we will fix later, and a bunch of interesting lines about the HTTP server launching. The line You can view the site at http://localhost:8080 sounds promising. Open that URL in the browser and you should see the first version of our blog:

The implementation of the first page

Now that we know what the code does, we can go through each part individually.

First, we start with a regular namespace declaration, which contains our use and require declarations:

(ns blorg.core

(:use noir.core)

(:require [noir.server :as server]

[hiccup.page :as page]))We use noir.core, which imports the function names defined in that namespace into our own namespace. This means we can refer to functions in noir.core with just their names, like we will use defpage.

require loads just the namespace and does not import the functions. We can refer to names defined in the namespace with the syntax namespace/name. (require 'noir.server) would let us call noir.server/start-server. As a convenience shortcut, we give shorter names to the namespaces we require: noir.server is just server (so we can say server/start-server) and hiccup.page is just page.

Next, we define some blog posts to display on the page:

(def *posts* [{:title "foo" :content "bar"}

{:title "quux" :content "ref ref"}])The * characters are an idiomatic way to indicate that a name is dynamic, and is a mistake on my part here. We saw that Clojure actually warned about this; we’ll change the name soon.

At this point, we have decided to represent blog posts as maps with a title and the content of the blog post. Because using maps in Clojure is so simple this representation works well without introducing boilerplate.

Satisfied that we can now represent blog posts, we define our web page:

(defpage "/" []

(page/html5

(for [post *posts*]

[:section

[:h2 (:title post)]

[:p (:content post)]])))We use noir’s defpage to define a page located at the URL /. It contains a HTML 5 page that lists all the blog posts in their own <section> tags. We use Hiccup to write HTML as Clojure vectors; the page/html5 function will turn our vectors into HTML strings that are returned to the browser. For an example, the vector [:p (:content post)] is roughly the same as (str "<p>" (:content post) "</p>").

We use a for loop to turn each post into a vector. for is Clojure syntax for a list comprehension. The simple form of for we use here could be written as a map call as well:

(for [elem elems] (...))

(map (fn [elem] (...)) elems)However, the for is more readable in this context. With map, the defpage call would look like this:

(defpage "/" []

(page/html5

(map

(fn [post]

[:section

[:h2 (:title post)]

[:p (:content post)]])

*posts*)))The last function in our file is -main: it is the function Clojure calls when we run the application with lein run.

Adding new posts

Our first version of the blog was a good demonstration that we knew how to wire together the libraries we use (noir, hiccup) and how to use them to render posts to users.

Next we would like to add a feature to the blog that make it actually useful: adding posts. We’d like the blog page to always show, at the bottom, a form for adding a new post. The form should have two input fields: one for the title of the post and one for the body content. The form should also have a submit button that adds the post to the list of posts.

Check out the state tag:

git checkout stateImplementation requirements

We need to implement two things: the form on the blog page, and an endpoint that the form is POSTed to by the browser.

The form

We define the form in its own function for clarity:

(defn add-form []

[:section

[:h2 "Add post"]

(form-to [:post "/"]

(label "title" "Title")

[:br]

(text-field "title")

[:br]

(label "content" "Content")

[:br]

(text-area "content")

[:br]

(submit-button "Add"))])We’ve put the form in its own <section> tag, and we use hiccup.form’s form-to function to define the form. The [:br] vectors make sure the form elements are properly vertical.

If you think this definition is a bit ugly, you’re absolutely right. We’ll fix it soon. However, we don’t yet have any way of delivering style information with CSS to the browser. This was the quickest way of adding a form, which we need right now to test the adding of posts.

The end-point

We declare a new page with defpage to handle the POST submission from the form:

(defpage [:post "/"] {:keys [title content]}

(swap! posts #(conj % {:title title :content content}))

(response/redirect "/"))The first parameter to defpage, [:post "/"], declares that this page handels only HTTP POST requests. The second parameter, {:keys [title content]} extracts the title and content fields from the POST request.

The next line adds a new post to the vector of posts. To understand it, we need to introduce a new syntax form and a new concept.